Brewery Green, The Tetley, Leeds (photos: Jon Price)

In another of our occasional series of guest blogs on artistic leadership, Brussels based musician and philosopher Kathleen Coessens asks how we can think about leadership from the perspective of the artist, whether the artist can be a leader, and – if so – what kind of leader?

Kathleen, a participant in our Brussels seminar during On The Edge’s Cultural leadership and the place of the Artist project in 2016, looks back to that discussion through the lens of her own artistic identity and three productive metaphors.

As always we invite further responses to continue and connect our thinking.

Let’s start with a mainstream view on artists. Artists are wonderful people, but special, even marginal. An artist seems to create his/her own world, distanced from societal pressure and expectations. Artists don’t participate fully in the routines of the everyday organization or in productive cultural processes like economy, politics, health-care, education, ecology. Often considered as an outsider, the artist lives at the periphery of society and seems thus far away from participating in cultural leadership. However, the discussion at BOZAR in Brussels during the Cultural Leadership workshop in July 2016 opened interesting reflections and considerations for the true potential and need for artistic leadership. This text continues these reflections and will look at the artist as a flâneur, as a gardener and as a physician: three perspectives from which a view on artistic leadership can emerge.

The artist as flâneur

Present inside urban time and economic needs, but always slowing down to experience less visible sides of life and as such escaping imposed time and space frames, the artist can be considered as the ‘flâneur’ of Baudelaire and Benjamin.

The flâneur observes and is sensitive to all the noises, colours, chaos, heterogeneity and complexity of the surrounding environment. In analogy with the flâneur, the artist is not only a wanderer and observer of the outside, but also of their own inside, of their own thinking and imagination. Both the artist and the flâneur resist the temptation of the prevailing ideology – be it the city or the knowledge economy – and develop other perspectives, different aesthetic encounters and possible sources for creation. They have no explicit strategy of reversing the order of things, but explore small moments of resistance and tactics of rebellion. For the flâneur, these acts stay at the level of their own conduct and ideas and the impact remains the impact of an individual actor in the mass of humans.

But, different from the flâneur, the artist searches for an aesthetic output that will have public exposure, not in the political sense, but in the cultural sense. This seems to be in contradiction with our perspective on the artist as a lonely flâneur. While not fully participating in the main productive processes of society, nevertheless, the artist’s impressions, tools, questions and creations are embedded in the environment and offer a reflection or response on specific impressions and issues of that environment. The impulse for the artists’ creations is both the inside and the outside, both the individual and the societal, both the material and the living. The artist always communicates.

Le Botanique, Brussels

The artist as gardener

In the first place, the artist does not only observe, imagine or reflect upon the outside world – like the flâneur – but he or she (re)creates the outside world from their own inside, merging both in the act of creation. The complexity and profundity of an artwork reflects an individual answer to the outside, or to the way both inside (the artist) and outside (the world) are related. You can compare the artist to the gardener for whom the garden is both inside and outside, a personal process and passion as well as a shared outcome and result, both necessary and aesthetic. The earth is laboured, treated, reworked, out of need and imagination, out of pleasure and for production; it is cultivated and leads to a visible output. The human relationships around the garden are precious and open, and the work often invites free participation and appreciation.

This means, secondly, that the output of the artist has public exposure: the artwork. In that sense, the artist’s answer to society is not universal, but is nevertheless an individual instance of a potential universal statement, as it is not only one unique response of a human experience, but always open to the judgment of an audience. By exposing their own work, the artist exposes him or herself and becomes vulnerable, potentially admired or rejected. The work can be debated, criticized, interpreted in different ways, opening up new reflections. The answer of the artist will be another artwork, and a subsequent range of artworks as further processes of capturing some aspects of the human condition in the cultural world, responding again and again to the confrontation of inside and outside, individual and society.

The artist as physician

Indeed, taking care of a garden is a continuous process, a never ending work that has to take into account the obstacles of the material — the earth, the living — the plants — and the climatological conditions. This means that, thirdly, two fields need always to be joined: that of the living and that of the material. Think of a physician: (s)he cannot escape human interpretations, personal stories, the individual body, while (s)he needs to apply a general medical knowledge that will never have the same effect on different patients. The artist, like a physician, has to join different domains of knowledge, both know-how and know-that, both of materials and of the living, both tacit and explicit. It is in the exchange, or rather in the extension of the human body and in a passion for human and material relationships of a special kind, that artistic processes develop. Joining these two fields means a deep understanding of both, not only of an intellectual, but also of a sensorial and embodied kind. The artist will look upon the affordances of things and actions, of their relationships and possible interactions. In that sense, the artist acts like a physician: looking carefully at the organs of a patient, listening to the story behind, analysing both the mental and the physical, and then, realising a judgement that is a combination of the living and the material, the individual and the general, the story and the science. Like the physician, the artist needs a lot of craftsmanship, know-how and know-that.

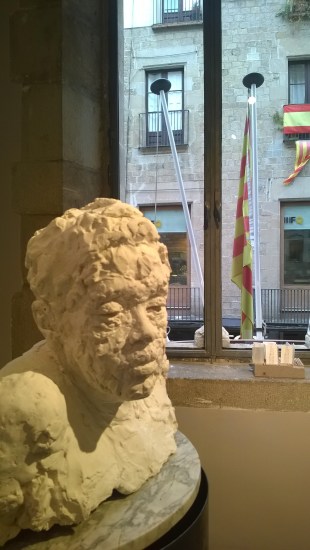

Berta Blanca T Ivanow: Madame X study (Fundació Güell sculpture prize at Reial Cercle Artístic de Barcelona, 2016)

Craftsmanship can be developed by rigorous work, discipline and passion. Art after all is a slow science: it takes time, asks for time, lasts over time. The becoming of art, the process of creation, is for the artist the main preoccupation and each artistic output is but one step in that continuous process. The artist needs the quality of listening: listening to the previous artists, to the master, to the tradition. At the same time, the artist needs the quality of creation: to create anew and to become again an artist. Humble and proud, rebellious and respectful, patient but dynamic, the artist relies both on imagination and on reality.

The artist as leader

Let’s come back to the artist and leadership. While observing and questioning society in a different tempo and from a holistic perspective – sensorial, embodied, intellectual – can be considered an interesting capacity for leadership, the flâneur is clearly not a leader, because of the individualisation of such an attitude. However, the artist opens an immense potential of affordances for leadership, adding to this capacity a lot of other qualities: public exposure, vulnerability, slow science, craftsmanship and a deep understanding of the living and the material. The artist dares to confront an audience with new ideas and material realizations that benefit reflection and understanding of society. The artistic reflection and consequent action becomes a literal point of view: people can hear, see, experience it and can argue and respond in both intellectual and/or emotional ways. The artist does not impose but proposes, presents. Moreover, like the gardener, the artist presents his or her own views – often as a response to aspects of the environment – in a vulnerable way and therefore opens up potential answers, critiques and different interpretations. By being both respectful to tradition and open to new ideas, the artist is capable of linking past and future. Like the gardener and the physician, the artist can face the future only by taking care of the present.

Finally, the capacities of merging, interrelating and exploring continuously the relationships between human action and experience and the affordances of the material – between detailed, micro-scale and holistic output – offer the artist a capacity for insight that is crucial for leadership.

Leave a comment